The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Energy or the United States Government.

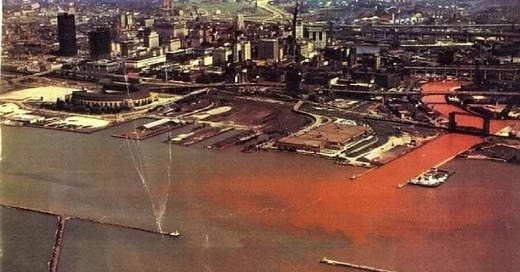

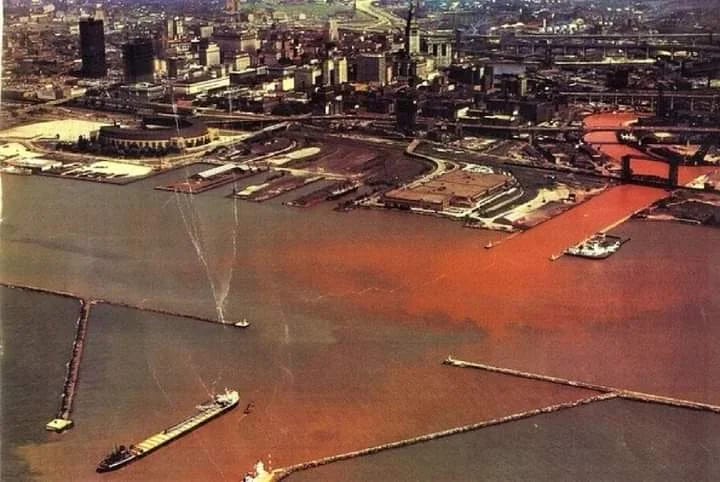

Many often forget just how bad industrial pollution in the US was during the second half of the 20th century. The post World War II boom spurred plastics and chemicals manufacturing, along with the coal power plants to support the rapid load growth occuring across the country. But this rapid, unchecked industrial development came at a cost: smog regularly blanketed major cities, while polluted waterways were known for turning unnatural colors and even catching fire due to the uncontrolled release of waste from factories.

The US government responded to public pressure with a flurry of legislative action: the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, the National Environmental Protection Act were all passed in a short span of time, with bipartisan amendments made to strengthen provisions across administrations. The backlash to these externalities also incubated the modern environmental movement today and the modern negative connotation of “chemicals”. And while many of these provisions were successful e.g. performance based standards, phase outs of ozone depleting chemicals, and cap-and-trade markets like those used to eliminate acid rain, it also locked in environmental proceduralism which today hinders much needed clean energy development.

Industrial development is not bad! Factories produce valuable products, taking scientific innovations and producing them at scale for the everyday consumer. But the lesson from the 20th century is that unchecked externalities can lead to enduring societal backlash and regulations with unforeseen and long-lasting consequences for the future.

AI is increasingly becoming industrialized, poised to deliver valuable services and play a crucial role in our economy. A useful metaphor to understand its societal impact is to view AI as an industrial system, with synthetic AI data akin to industrial pollution. Just as unchecked industrial processes can lead to environmental damage, the uncontrolled proliferation of AI models and their outputs risks creating digital pollution.

Our digital economy (Web 2.0) today is organized around platforms that organize information to allow serendipitous discovery of mutual interests between people (e.g. Tumblr/Pinterest, Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, Twitter). It is these internet common spaces that are the same ones at risk from AI pollution.

Already, we are starting to see the creeping in of synthetic data pollution: most william morris paints on etsy are AI-generated1, disillusioned dem voters on twitter are actually LLM bots, etc.2 The promise of the internet - a place where people all over the world can connect and find one another based on any set of interests - is slowly being overtaken as AI pollution begins to clog the feeds and bots becoming increasingly swarming on forums.

The negative externalities of scalable digital pollution are not new: the death of phone polling is because that channel (phone calls from numbers you don’t recognize) is completely saturated from spam pollution already.

What happened when one channel was clogged with pollution? Existing aggregators (e.g. voting polls, economic surveys) become much less accurate and start shifting to other sources e.g. web-based. But even then, there were subtle costs to retreat from one platform or channel to another. As kyla scanlon puts it:

And we see this pattern repeat itself: in response to the growing swell of AI pollution, the walls are coming up.3 We’re returning to closed ecosystems, like group chats and private discord servers, and regressing to networks facilitated by personal connections. The promise of the internet is dying and what we will all be left with is unclear.

And just like with pollution, exposure is unequally distributed. Those who understand the pernicious side effects of the attention economy will take steps to mitigate them, while those without will be naively exposed to less and less authentic content and connection - “feeds for thee and not for me”.4

But it doesn’t have to be this way. We could have robust AI verification systems and require every bot on forums to be registered and clearly labelled; we could have social media platforms with active moderation teams that clean up the feeds. But the dominant platform network effects and AI hype cycle means there is, as of now, little competition or incentive for better digital pollution management on platforms.5

This is not the first time the worlds largest companies have rushed headlong to develop and deploy new technologies at breakneck speeds, hoping to win new product markets. Nor is it the first time industries have generated significant negative externalities for society. Perhaps the history of the environmental movement and the mistakes of past industries can offer a helpful motivation, and a warning, to AI developers today.

another example of “AI slop”

One interesting analog example is how prolific archaeological fakes by one artist made specific mesoamerican historical study near impossible.

The early internet left a pristine, if incomplete fossil record. But the digital record today is increasingly corrupted by invisible microplastics, digital artifacts sprinkled into the record that are increasingly hard to detect.

For an international example, China’s digital environment could be thought of as a greenhouse monoculture, while the US’s an overgrown hedge.

Along with an entire spectrum in between e.g. those who willingly, or without other choices, opt into “AI girlfriends”. But it remains to be seen whether having that option leaves someone better off in the long run.

While I think the analogy of synthetic AI data as industrial pollution is helpful, I don’t think it offers analogous policy solutions. Those ideas will have to come from elsewhere. If only there were more technologists who earnestly grappled with understanding the nuances of federal policymaking coming up with concrete policy solutions to address externalities from AI pollution, as opposed to other kinds of supposed externalities!

This is a good metaphor!