Why I quit working at an AI startup to join the Department of Energy

Identifying impact arbitrage in working on climate

The views expressed in this blog are entirely my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Energy or the United States Government.

I recently changed jobs!

In this post, I want to share about my experiences thus far on the journey from being a ML Engineer at an AI startup to working in the Department of Energy (via ORISE).1

Working at an AI Startup

Honestly, I did not do the appropriate due diligence when accepting my first job out of college. But I was fortunate to land at a well-funded, fast-paced, and innovative AI hardware accelerator startup as a machine learning engineer.

During my time there, I was able to work on one of the handful of teams in the world that not only deployed and ran large language models but did so while building on top of an evolving hardware and compiler stack.2 While many of my friends in big tech who started their jobs around the same time as me talked about how they were still writing bash scripts 6 months in, I was given opportunities to take ownership of specific product verticals and building my own models (and experience the challenges of finding product-market fit within the AI hardware and cloud ecosystem).

In addition to being able to work on Very Cool Things™, I also learned a fair amount about company culture building, specifically around building teams that could execute and iterate quickly. I saw how a company builds culture through top-down messaging from all-hands and how to tie company values to day-to-day operations.

All this to say that I’m very grateful for my time there and the things that I learned, both technically and more broadly, about building culture and how to manage teams.

Working on Climate

During this time though, I was also thinking deeply about climate change: about the decarbonization pathways we needed to hit and where my personal skills and experiences could bring the most leverage.

I arrived at 3 possible paths for me to align my work with the climate crisis, all of which I explored fairly extensively: bringing my AI skills to a climate-tech startup that meaningfully used AI to directly drive decarbonization, running for state office, and working in the federal government.

I think working at a startup is self-explanatory given my background (and the backgrounds of most of my readers). Many of the metanarratives and worldviews floating around today already frame startups as the best vehicle for impact and the coolest thing to do. Running for state office is something to talk more about another time, but I’m guessing that for many people, working in the federal government is not something we would consider as high leverage.

I’ll be upfront: I believe the federal government has an important, indeed critical, role to play in climate change. As long-time readers can perhaps tell, I’ve been thinking about state capacity and how government funding shapes the technology we eventually develop. I won’t take the time to try to argue for this theory of change, because I think most people at least somewhat accept the government is important. The issue is not about the impact but more often along the lines of: “it’s too slow,” “it’s too bureaucratic and political,” and “the pay sucks.”

These can all be true (see below for more details). But my conclusion is, that’s why its a great place to work!

There is a common piece of advice in silicon valley to go “find your people”: identify like-minded communities of talent and energy and plug yourself into them. That may be good advice, but I have an opposite perspective: find underleveraged areas of impact and bring your attention to bear in these areas.3 This is a form of impact arbitrage: go where the people aren’t. In my (admittedly biased, mostly Bay Area) circles, I knew so many people who wanted to start a startup and increasingly, many of them wanted to start a climate-tech startup. That's a good thing! But markets are also efficient - if everyone is going to do this one thing, what are the odds I can make a marginal impact there? Conversely, there is another path, one that almost no one I knew was doing and which had heavily misaligned incentives (poor pay, based in DC, no equity). I considered my chances of impact much better there than a path that everyone else already wanted to do.

Theories of impact aside, it also helped that Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) in 2022, which significantly empowered the Department of Energy (and other agencies, like the Environmental Protection Agency) to fund climate technologies in fairly novel ways. Given my position of being able/willing to take on these misaligned incentives and the unique growth happening at the Department of Energy (DOE), I decided to make the jump into the public sector.

Working at the Department of Energy

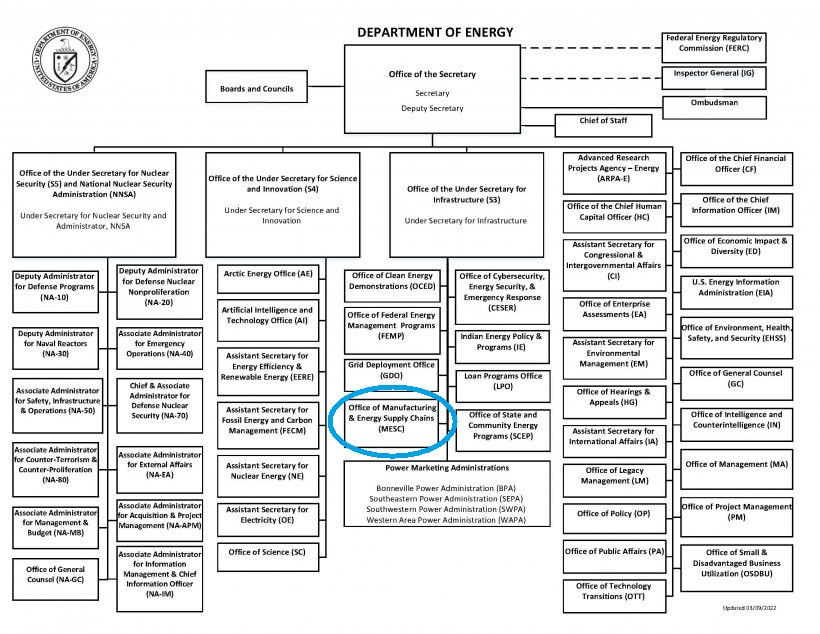

I’m located in the Office of Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains (MESC), which is under the Under Secretary for Infrastructure. The exciting thing is that not only is MESC a new office, but the entire Under Secretary for Infrastructure as a whole is new.

Historically, the DOE has been a science R&D shop. The US invented solar panels, lithium-ion batteries, and built the first nuclear reactors. Those were all invented in the US because of a strong science and technology ecosystem that was sustainbed by federal funding from the DOE.

But I think there is a growing awareness that while we invented all those things, we don’t build them here - American innovation did not result in American-made infrastructure or American jobs. So the DOE’s recent reorg, driven by the new funding authorities granted by Congress under IRA and BIL, is a pivot for the DOE to include demonstration and deployment4 in its porfolio of funding activities, in addition to basic sciences and research.

After my first month at the DOE, here are a few scattered observations about working there:

IT: ok yes, the IT can suck. I had to push to get the IT helpdesk to onboard me and I had issues logging into my laptop for the first two weeks. But now that those onboarding issues have been resolved, I have found myself managing to get by while trapped inside the belly of Microsoft enterprise software.5

And I got an iPhone 12 as a work phone - thats even nicer than my personal phone!justifying the bureaucracy: I think something people underappreciate about the federal agencies is that they have the most unique cash-flow structure of any organization. The form fits its function, and in this case, the function is totally unique and incomparable to anything the private sector does.

Most parts of the DOE, including the one I’m in, are essentially funding allocators. Congress authorizes the DOE to spend money on certain programs (which ranges from millions to billions of dollars per program) and the DOE is tasked with pushing that money out to a broad variety of actors ranging from national labs and academia to startups and big corporations and then managing those projects over time. There are no cost/profit centers - cash flow for each org is dictated in large part by remote political forces, which each office has only marginal leverage over.

With that said, I am still trying to disentangle what parts of DOE bureaucracy are inherent to any big business organization (which I’ve never really been part of), what aspects of its form are intrinsic to the unique function it plays, and what parts are just in need of modernization.program management: something I’ve written about briefly, which still needs to be expanded, is that program management is a unique, experientially learned skill. It does require hard technical understanding, but a program manager who only has technical know-how would not be very good at their job. Experiential knowledge around program design and stakeholder engagement are also critical to a programs impact. Particularly for large, coordinated projects requiring inter-office and inter-agency coordination (which is often the case for demonstration & deployment funding, as opposed to basic science funding), being an effective operator is just as important as technical knowledge. In hiring for federal employees (aka feds), the government tends to prefer those willing to give 5-year commitments, because each program takes ~2 years and you’re on the learning curve the first time and executing effectively the 2nd time. Now that I’m in the middle of these processes, I better understand why institutional history and continuity are more important in workplaces that require greater degrees of implicit, experiential knowledge (disclaimer: I am not a program manager, these are just my observations being around them)

talent: it is sad to hear many disparaging comments about the federal workforce, especially from those who knowingly or unknowingly benefit from the federal government’s support6. While I’m sure one's experience varies across the entire federal ecosystem, I’ll just say that in my experience interviewing with many different offices across DOE and working inside it now in MESC, I have been consistently impressed with the drive and seriousness of the people who work there.

I’ll also add that the DOE has the most demographically representative workforce of any organization I’ve been part of.suiting up: I had a mini-crisis about having to suit up for work everyday. In many parts of the DOE (e.g. national lab), its just business casual, but given my office’s current standing, jackets and tucked-in collar shirts seem to be the norm when in the office. It was not a small shift going from rolling out of bed in any t-shirt and tuning into an online meeting where everyone had their camera off, to collars, suits, and camera on.

But with further reflection, I’ve managed to convince myself that this is actually an appropriate and virtuous thing. It is fitting that the attitude of software engineers in silicon valley who "just want to build cool stuff" and don’t think critically about the impact and power of their work is consistent with the casualness in how they dress at work. Playing league and building ad pipelines to serve billions of customers are all pretty much the same from that perspective. So I have convinced myself that it is fitting to dress up for work, because the nature of the work is serious and I should convey that and remind myself of that in how I dress.7

Washington DC as a city:

DC culture: as one friend of mine in DC put it, the silicon valley hustle-and-network-to-raise-money-at-parties culture is really not that different from the coffee-chat-business-card-who-do-you-know8 culture in DC. The difference is that the former is because you believe you have a hypothesis that, if realized, will make you and your future investors a lot of money and the latter is usually a matter of conviction and passion about how to change the world (though both groups have tinges of attention or power seeking behavior). Also, it feels like DC is a small city socially, at least among young people in the policy world. That's something I’m still deciding if its an aspect of DC I like or dislike.

Similar to SF, it can feel like a cultural monoculture, due to the its obvious political center of gravity. But as I mentioned above, it’s a different set of motivations and actors, which lack some of the neuroses particular to SF.DC as a city: decent public transit, decent bike lane infrastructure and an extensive bike station network. In my opinion, it’s a clean, human-sized tier 1 city. Only thing it lacks is good asian food - for that you have to go out to the northern Virginia or Maryland suburbs. A very normal climate (as in it actually has 4 seasons but is never too crazy in any direction e.g. Chicago, NYC, Boston) and lots of cultural history (all the museums and monuments you could ever want). If DC just continues to build housing, actually starts to bring in good asian food, and Congress gives residents the right to vote, I think DC would be unstoppable as a metro region.

Overall, I think my time at the DOE thus far has confirmed the viability of public service as a high-impact career and has opened my eyes to a whole new set of operational skills for an individual and action space for how institutions operate and effect change.

And we are hiring! If you’re interested in joining the DOE as a new/early grad, you can check out Zintellect for many fellowship opportunities (which is also where my fellowship is hosted). If you’re interested in full-time roles (and also some internships), check out USAjobs. Feel free to reach out to me if you want to ask about more ways to join the federal government!

Disclaimer: I won’t talk much about the process of actually getting a job in the DOE, mostly because I think my path was fairly unique and thus not particularly helpful to others, nor is it interesting enough to write about. But if you’re still interested, you can infer a fair amount from my LinkedIn. With that said, there are plenty of ways to join the federal government (we are hiring!) - feel free to reach out if you’re interested and don’t know where to start.

I did realize ironically enough that because my job was so unique, there were very few other places I could apply to that would have equivalent job descriptions. The only other people building AI models on top of novel hardware were at Google, maybe Amazon, and other AI hardware accelerator startups. For just about any other ML Engineering role, debugging a model failing due to compiler issues was probably not high on the list of required experiences.

To their credit, the Effective Altruists, who talk a big game about finding neglected problems, have also identified policy as an important space. And again, to their credit, they have funded many channels to funnel like-minded people into the DC world, quite successfully. So there’s at least one other group that has the same theory of change as me!

Demonstration and Deployment (D&D) is the acronymized version of what some of the kids these days are calling “Industrial Policy”

I will say, I understand why organizations like Microsoft’s enterprise solutions. Enterprise B2B software is no joke and Microsoft has it down to an art (c.f. John Luttig’s argument that MSFT could be the first $10T company)

Easy example: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/innovations/wp/2017/03/16/this-government-loan-program-helped-tesla-at-a-critical-time-trump-wants-to-cut-it/

This is a similar line of argument used in debates around whether or not one should dress up for church

perhaps reflective of the different age demographic - business cards are definitely still a thing, as I keep finding out at work and at happy hours.