2 years ago, I quit my job at an AI startup to join the Department of Energy. Last week was my final week at DOE - more to come on whats next, but this is meant to serve as some public retrospective on my time there.

A few of the more impactful things I did at DOE on supply chains and critical minerals:

created the portfolio and allocation strategy for ~$10B in investment tax credits for clean energy manufacturing and critical materials.

articulated DOE’s stance on the 45X production tax credit for critical minerals. The final IRS rulemaking adopted our position, effectively doubling the value of 45X for critical mineral processors

(almost) created a critical material price support program1

In December 2023, DOE created a new coordination office for critical and emerging technologies, which included AI policy. A number of people around the building knew about my technical background in AI and so I got pulled in to help support this new office as well, where I:

launched DOE’s Frontiers in AI for Science, Security, and Technology (FASST) initiative (check out energy.gov/fasst!), DOE’s flagship initiative to provide a national AI capability through our 17 national labs

ran an AI seminar for DOE staff, to build technical understanding of AI within our applied energy offices

drafted DOE’s strategy to meet data center load growth in summer 2024 and helped stand up DOE’s data center response team

In other words, I spent 2024 working 2 jobs, while only getting paid for one of them - talk about government efficiency!

A Few Things I’ve learned about Government and DOE:

I worked alongside some of the most talented, hardworking people I’ve met in my career.

I did also work with many other people.2

I went from being a ML engineer at an AI hardware startup to a federal employee at DOE on the thesis that high-agency, technical people could make a difference in federal bureaucracy, particularly during times of change significant change e.g. CHIPS and Science Act, Inflation Reduction Act. I would say that thesis has been validated in full (and if you are interested in making a similar jump, I’m happy to chat)

But I still make less in nominal(!) terms after almost 2 years at DOE than my first pay check out of college. This was mostly the fault of HR not providing GS flexibility to hiring managers. I still have a very healthy salary I cannot complain about, but this kind of straitjacketed approach to hiring is an endemic problem in federal governments. HR needs to be brought to heel and hiring managers need to be empowered over them.3

DOE is a very misunderstood agency. Most people think of DOE as the “clean energy department”. Many of the (Democrat) political appointees who seek appointments in the Department are from that flavor. In reality, before the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act, the DOE budget for energy was ~$5B.

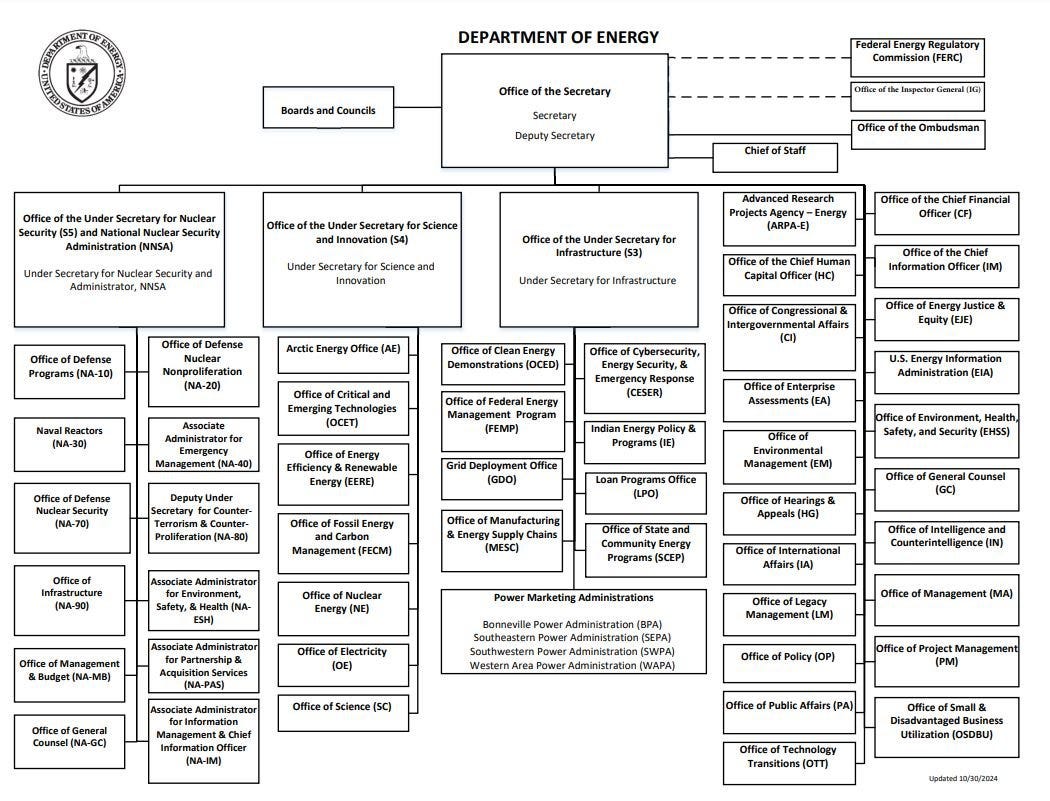

The majority of DOE’s budget actually goes to our National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), ~$25B for maintaining the nuclear weapons stockpile, support nuclear non-proliferation, and building the nuclear reactors in our naval submariens and carriers. DOE also manages our 17 national labs, which are the provide the backbone of scientific infrastructure for the US, including the world’s largest hard light sources, the fastest public supercomputers, and our own semi fab.

A more accurate representation of DOE:

But post Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act, DOE grew a new appendage: the Undersecretary of Infrastructure, which includes the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED), Loan Program Office (LPO), and Office of Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains (MESC). Think of this as the “industrial policy” arm of DOE, rather than the R&D funding in the Undersecretary for Science, which was DOE’s traditional energy remit. I had the privilege of working in both undersecretaries and experiencing the cultural differences in the people and the differences in mission.

Org charts are a great way to understand how an organization functions. But nothing makes an org chart obsolete faster than the unequal distribution of competence. Entire offices have fallen off the org chart due to this. It is difficult to quantify “inefficiency” from an org chart alone, without understanding the people behind the org chart.

Understanding how bureaucracies work (or don’t work) is a key skill. Arguably, the key bottleneck for big tech companies like Google and Microsoft is not a lack of technical talent, but a poor understanding of how to properly manage and incentivize bureaucracies. Conversely, the success of people like Elon Musk and Hyman Rickover is precisely that they understand how to effectively operate and build organizations that function and achieve their stated purpose.

Credit allocation in public policy is really hard. Who is responsible for a certain change in a tax credit or export control? And who was working against it? If you read the news, your perception will be wrong. People hire lobbyists to understand these illegible factions. This is also why DC will be the last city to be automated. It is ultimately a city that relies on invisible networks of interpersonal trust to get things done.

The politicization of industrial policy and the uncertainty it generates across the 4-year election cycle hurts the effectiveness of industrial policy. For instance, political uncertainty means manufacturers lack the long-term incentive to invest in new plants. I have been in conversations where battery companies tell us “we have no intention of buying from American sources because we do not believe there will be any fiscal incentive for us to do so in 2 years (in reference to 30D and 45X)”. We need a true, bipartisan consensus on the tools of industrial policy if we are serious about onshoring supply chains.

This uncertainty also influences how companies think about tradeoffs between taking grants, loans, investment tax credits, and production tax credits. It is not as simple as picking a 30% CapEx discount over a 10% OpEx discount; companies weigh subsidy timing, political risk, and oversight requirements for tax credits vs grants. I wrote a bit about this previously with

The Diff in 2023 (paywall).Congress often passes laws like “you must take Y obvious factor into explicit consideration” or “do X in Y time” but they often backfire.4 A few examples:

the “paperwork reduction act” required any government office to check with the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) in the White House every time they wanted to put out a form, to ensure the form was not duplicative of any other existing form. This measure aimed at “reducing paperwork” from the government, has indeed accomplished its goal, but by making it impossibly slow for any government office to put out any form or survey. This hurts everything from website user surveys to USGS surveys of opinions around public lands.

I designed a Request for Information (RFI) while at DOE on energy supply chains that was the first to use “online portals” to collect responses in a systematic fashion that could be directly organized into a spreadsheet, rather using an email inbox to collect pdf responses from companies. The portals were really just Microsoft Forms™, but we had to take care not to call them that because saying “form” triggers PRA review. Having our lawyers ensure we did not trigger PRA review delayed the rollout of this by 9 months.

The 1984 Competition in Contracting Act requires government agencies to ensure all government contracts are competitively run. But this enforcement of process for achieving a certain aim e.g. “competition”, in reality slows down agencies ability to execute and creates its own litigation doom-loop, akin to what we see in permitting.

When I first joined DOE, I was tasked with procuring a data vendor for supply chain analysis. When I was told it would take 6 months to compete a contract, I tried looking for faster routes. In particular, I thought it would be better for the agency, and the taxpayer, if we worked with other offices to procure these services, including riding on existing contracts through an expanded order. This would in theory save us time, by using an existing contract, and save money, by buying a larger seat order for the department rather than office by office. This was stymied by other kinds of interoffice budgeting and politics. In the end, a year almost passed and we ended up going through a different work around to get some half-assed data access.

If I had known better, I would have just taken the 6 month hit to compete a contract, and leave other offices to procure their own services. This kind of legislative method of “achieving-outcome-by-process” is incredibly frustrating when you are the person on the inside trying to accomplish something. Similar to risk aversion - we cannot blame agencies for being slow or hiring poorly while at the same time straitjacketing them with process that assumes a worst actor model of the executive branch.

This was an issue for a minor service I was tasked to deliver. But it is the same issue at root of why defense contracts are absurdly long and part of why DARPA has lost some of its historic independence.

There is this notion that putting a shot clock on permitting agencies will speed up agencies. As if Congress telling an agency “do the exact same thing but faster”, without any change in statute or additional funding, would actually change outcomes.

At Deploy24, I hosted a private roundtable on repowering energy infrastructure for load growth, which included several hydropower developers. Hydro developers have some of the most onerous permitting + licensing regimes for any energy development. One of those that is required for every hydropower dam is a Clean Water Act section 401 license, which is delegated to states. In the original law, it explicitly includes that states must provide a license decision in “a reasonable period of time (which shall not exceed one year)”.

Despite this, I was told point blank by a hydro developer: “we do not use the shot clock. If the agency is coming up on one year, we pull out our application and resubmit.”

When I asked why, they said: “we don’t want to be the first one to stand out on this provision and test what happens”. Much of this is driven by the uncertain litigation around this particular shot clock but is symptomatic of how legal uncertainty, created by an permissively litigous rule of law and courts, makes permitting reform filled with subtle nuances that can stymie even seemingly explicit legal tweaks.China learned these lessons long ago:

1. “local officials learned that to attract foreign factories, they had to set up ‘one-stop’ decision centers. Early foreign investors had been frustrated by having to deal with different government bureaucracies….by the mid 1980’s the areas that were attracting the most foreign companies were those that had been able to reorganize and centralize decision-making so that officials could make all key decisions from one office”

2. “Officials in localities that competed for investment funds learned early on that if they did not allow the outside investors to earn what they considered to be reasonable returns on investment, the investors would go elsewhere.”

3. “If local officials wanted an outside partner who would expand his investment, they had to be reliable…local officials found that the Chinese localities that did well over the years were those that honored the agreements. Not surprisingly, foreigners were willing to continue to invest when they found groups of local officials who were reliable and could resolve, creatively if necessary, all the unexpected problems that arose…”If you are interested more in learning about permitting, you should subscribe to

Green Tape!

Government reports serve many purposes. Congress loves to request them because they’re “free”. In many cases, the value provided is less the content and more so forcing an entire agency, or even interagency, to spend time thinking about something and coming to an agreement on it. It is a low-effort way to signal to agencies they should be doing more on something, without actually requiring or paying for it, and the congressional sponsor can take the content of the report as authoritative to lobby for some policy or solution.

(You might say Congress is trying to prompt a federated intelligence model, composed of many sub-agents, to think harder about certain topics…)

I did write several reports, none of which were mandated by Congress:

interagency report on a self-driving lab workshop [you can read this for more on self-driving labs]

AI for Energy report (required by Biden AI Executive Order)

Mapping Critical Minerals report (along with an associated GIS platform for critical minerals)

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, CHIPS and Science, and Inflation Reduction Act will be seen as once-in-a-generation, transformative investments in American infrastructure and manufacturing and the Biden administration deserves its credit for passing these.

That said, my personal experience with the Biden admin is 1) this white house was staffed by shockingly few people with actual experience in a federal agency, and it showed; and 2) there were way too many lawyers and consultants serving in high-level political appointee roles who didn’t know what they were doing. In particular, many did not understand how markets and industries operate and make decisions, which was particularly frustrating when we are trying to use federal incentives to shape markets and convince industries to decide to onshore.

Secretary of Energy Chris Wright is the first engineer to be appointed Secretary of Energy in over 30 years, as opposed to an academic or politician.5

There is an unfortunate policy innovation theater that happens in DC around new ideas. Everyone loves a new acronym, a new program, a new idea to serve as a blank canvas to get your specific idea or interest group into. This often wastes significant energy into building a “new thing” when there are existing vehicles that could be tweaked or improved that would have served the same purpose.

Federal employees are barred from writing about their work to avoid the impression that personal opinions are influencing policy decisions (specifically that executive branch is biased in its implementation of congressional statutes) and to avoid information leakage ahead of sensitive policy decisions.

With that said, expect to see more writing from me this coming year!

Many people blame agencies as being risk averse. In reality, there is a political economy of partisan gamemanship that does its best to magnify and distort any failure by an agency. Is it any surprise then that they are so risk averse? They are merely responding to the incentive structure they face from the media + Congress. We will not have bold, risk-taking offices and agencies until we depoliticize failure.

One job archetype I was surprised to learn about in DC is the “special assistant”. These are the most junior political appointees, usually fresh out of college and fresh off the campaign trail. They are placed within offices to help make sure different workstreams are on track and can double as a scheduler/making sure their principal is prepped for events. They usually report the chief of staff and, if they do their jobs well, can advance to a more senior policy position. This system is in part why DC has so many poli sci majors who do not know anything about the field they work in, but have become ingrained in the bureaucracy and intimately understand how it works.

Why do we have this system? Because special assistants create a political backbone across a federal agency that has value alignment with the administration. This value alignment is tested and proven out by their willingness to work long hours on a campaign for the candidate. They serve to ensure every part of a Department is appropriately prioritizing the political objectives of an administration. Not every agency has this arrangement e.g. NSF does not.6

Sebastian Bensu’s “Lieutenants are the limiting reagents” post is doubly true in political systems, particularly because the “principals” in government are usually not in their position by virtue of expertise or competence, but by their vote winning or political connections.

If any of this sounds interesting, I’d highly recommend making the jump into the policy world! And if you want to learn more,

Statecraft is hands down the best place to hear first hand accounts of the inner workings of government and how they can have an impact.I am not the only civil servant who worked nights and weekends on a high-priority project, only to see it killed at the last minute by political appointees.

But there is a plan in place if the Trump administration wants to do critical mineral demand-side price support!

DO(G)E fired all DOE federal employees on probation last week, which covers employees who became federal employees (e.g. convert from contractor roles), started new roles, or got promoted in the past year. In a completely predictable turn of events, all of the best people I worked with at DOE were fired. The “deep state” lies unscathed.

A recent Astral Codex Ten article explains some of this dynamic quite well:

The most recent engineer to serve as Secretary of Energy in my estimation is James Watkins, who was appointed under George H.W. Bush. Before becoming Secretary, he was a Navy Admiral, the Chief of Naval Operations, and earlier in his career served under Hyman Rickover in Naval Reactors.

One anecdote about special assistants: when I was working on the final draft of the 2023 Supply Chain Progress Report, we were under a time crunch to get it through concurrence i.e. the process whereby every office signs off on its publication. My special assistant: “tell me the remaining offices we need concurrence from and I’ll talk to their front offices and make sure they know this is a priority”. Special assistants all know and socialize with other politicals across the agency, forming a backbone for political decision making and communication.

certified GOAT

this was so insightful! super interesting to see an inside perspective on your time at the DOE