Searching for Knowledge in the Digital Realm: Reflections on Learning Online

Catfish Noodling, Priors, and Embodied Knowledge

I spent my 2021 Summer working at Department of Energy ARPA-E studying quantum computing technology and markets. I’ve also spent the past year at Actuate Innovation exploring how to design DARPA-style climate programs in areas like mass timber and carbon removal. All this required gaining deep understanding of fields I only had incidental or tangential prior knowledge of, mediated in large part through digesting information online. Here are some reflections and distilled lessons I’ve learned over multiple forays for knowledge in the digital realm.

Searching the Internet as Catfish Noodling

Google, and many idealistic proponents of the internet, like to portray themselves as creating a single endpoint to easily access the breadth of human knowledge. But as hard as we might try, the internet, and all the multiformatted knowledge in it, refuses to be flattened into a single API.

Rather, the digital realm requires careful navigation and insider knowledge. It takes time to understand the lay of the land of a particular field: who the experts and relevant actors are, what their particular ideologies are and the associated philological tells1, the particular history of ideas and interdisciplinary connections. It also takes time to find the backdoors and hidden repositories that hold storehouses of knowledge2. Sometimes, those doors are locked, so you’ll have to find ways around them. It takes time to curate a useful and diverse stream of information across platforms: subscribing to seminars on Youtube, finding the right people to follow on Twitter, keeping an eye on possibly useful communities on Reddit.3 Internalizing these ecosystems of information is the antecedent to being able to begin to formulate theses to interesting questions like “what is the technical viability of useful quantum chemical simulations on a NISQ quantum computers” and “what are the barriers to mass timber adoption in the southeastern US”.

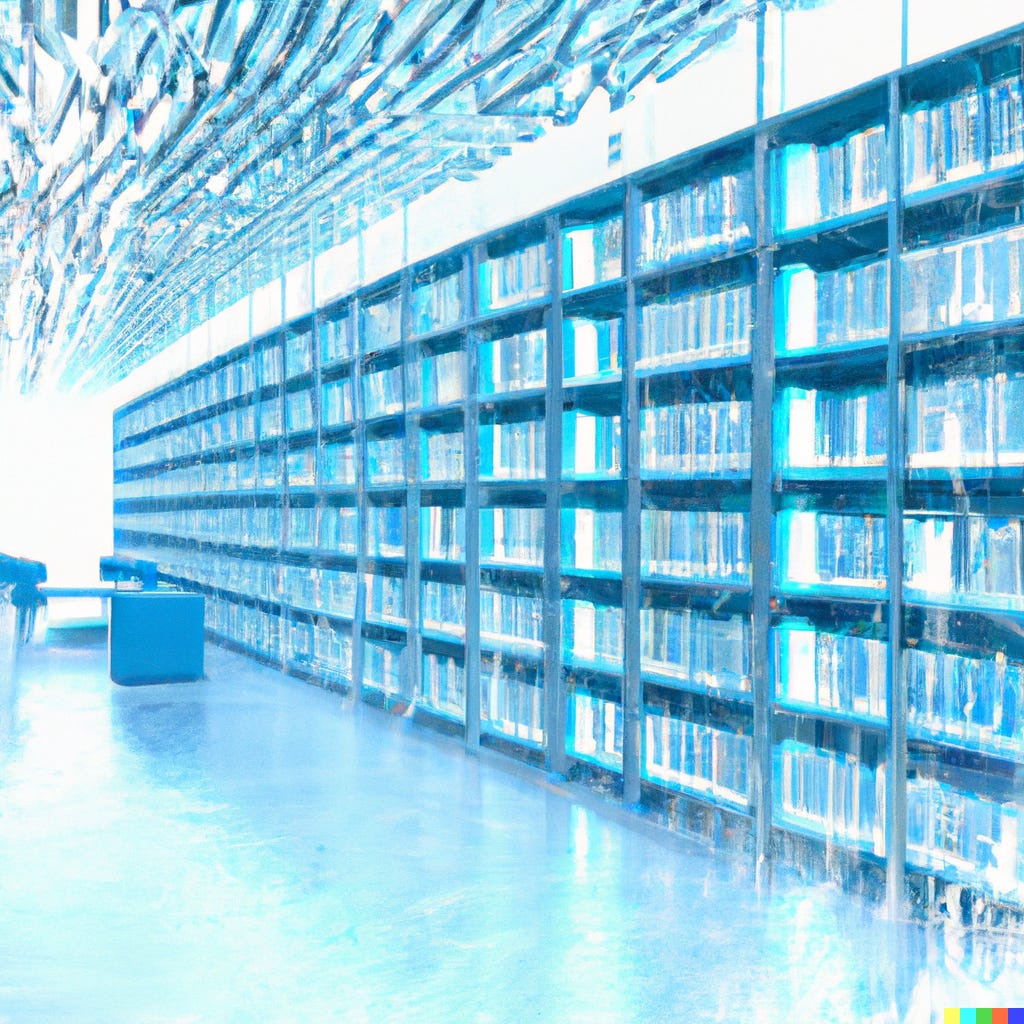

Grasping at the answers to such questions isn’t as easy as a single google search. Instead, the truth is slippery and vague. Sometimes you find a handy guide, only later to realize their particular flaws and biases have led you off the path. It requires digging into different crannies, diving into muddy waters where the path forward is unclear, filled with branching possibilities and contingent futures. And when you think you have it, a new piece of information enters the puzzle and you’re lost again, in need of re-evaluation and reorientation. Searching the internet is less like a digital library, with orderly, systematized catalogs of knowledge, and in many ways, more like catfish noodling. You’re digging around in murky waters, sticking your hands into different nooks and crannies in search of a catch. Those who are familiar with the waters know the best spots to look and how to avoid getting bit. Ultimately, it’s hands-on, grimy work that few are willing to do.

And where are the catfish hiding? In my experience, much of the worlds information is actually hidden, nestled in innocous government websites, usually in long PDF’s that nobody reads. So perhap’s its best to close with this ode to the humble PDF:

That’s why every morning, sometimes before breakfast, when I am in despair, I remember the three letters that always bring me comfort: PDF. And then, when I can, I go digging. I read about Gato, a new artificially intelligent agent that can caption images and play games, or the mathematics underlying misinformation, or “digital twins,” which are simulations of real-world things like cities that consulting firms seem able to sell these days. One site, scholar.archive.org, has PDFs going back to the 18th century. It’s empowering to look for this stuff instead of waiting for it to be socially discovered and jammed into my brain.

This was the original function of the web—to transmit learned texts to those seeking them. Humans have been transmitting for millennia, of course, which is how historians are able to quote Pliny’s last tweet (“Something up w/ Vesuvius, brb”). But the seeking is important, too; people should explore, not simply feed. Whatever will move society forward is not hidden inside the deflating giants. It’s out there in some pitiful PDF, with a title like “A New Platform for Communication” or “Machine Learning Applications for Community Organization.”

Utilize First-Principles Thinking to Test Hypotheses and Claims

Please don’t ask me what first-principles thinking actually means, everyone keeps using the term and I’m just bandwagoning. What I think I mean by first-principles is probably a combination of “use basic scientific knowledge to fact-check claims” and “generalize historical trends and patterns to existing novel developments”, which makes it somewhat of an overloaded term.

It might be easier to explain by way of examples:

When evaluating different carbon removal technologies like direct air capture, everyone should do a basic thermodynamic energy analysis, combined with some plug-ins for electricity prices. This will immediately clear away a lot of hype with some hard physics and also point out what are improvable cost areas and what is thermodynamically limited (or needs to be addressed through non-technological methods e.g. there is fundamental adsorption energy required for CO2 sorbents, but you can pair it with waste heat and get it for “free” in market terms, if not thermodynamic terms)

In my introductory undergraduate material science class, we had a homework problem calculating hydrogen diffusion through steel4. Combine that value with estimated leakage rate of methane in pipelines currently, the global warming potential of hydrogen in the atmosphere, and suddenly hydrogen networks need to be approached more thoughtfully and carefully than natural gas utilities would like us to think.

Understanding ideas like cost curves and the history of monocrystalline silicon wafers for solar panels is useful when evaluating a technology with multiple different paths e.g. quantum computing hardware5

An instructive example is energy storage: there are basic chemistry facts (lithium atoms are much smaller than sodium atoms, so they can be packed more densely), basic chemical market facts (sodium is cheaper than lithium), and then more complex trends around cost curves (namely, lithium has been on a learning curve for decades, while all the other battery chemistries are just getting started and making batteries, like making solar panels, is hard). These by themselves don’t give a full picture, but they provide a quick way to understand certain market trends.

Basic understanding of physics (E=mgh) and understanding what a concrete foundation is would have predicted Energy Vault’s much hyped gravity-based storage would fail. And lo and behold, they have now pivoted into…lithium ion batteries

Basic energy calculations will tell you:

cars are extraordinarily inefficent means of transportation, both energetically and volumetrically on a per-person basis

which limits their throughput for transportation

Neither of those facts change significantly with electric cars

Evaluate Priors (and Incentives) of Sources

“All models are wrong, but some are useful”

When evaluating any source, it is useful to determine what their priors and incentives are. Academics, VC’s, startup founders all inhabit particular types of spaces that determine their priors and how they communicate information. None of this is attributing maliciousness, but is simply recognizing that we are a product of our experiences. For instance, when I was studying quantum computing I quickly learned to discard any report by a VC but found conversations with academics useful, because academics have no need to make returns on investment, are often much more clear-eyed about the challenges difficult technologies face, and were much more likely to actually understand how the technology works, not just “quantum computers will solve problems exponentially faster”. VC’s were useful for understanding what the existing market trends were and what kinds of technology had access to capital, but I generally ignored their forecasts and use-cases.

Understanding different source’s priors is also a helpful way to resolve contradicting information from different sources. If you can step inside their priors and understand where someone is coming from, it allows you to be more thoughtful about what observations from them you keep and what you discard. Discerning someone’s implicit knowledge and understanding their motivations for why they went through the effort put their thoughts online is a useful way to understand how to rank-order information that’s coming in and where it fits in the overall picture.

Go Offline and Value Embodied Experience

The final lesson is that learning online is insufficient and limited. Contrary to the conventional wisdom in Silicon Valley, there is still only so much you can learn through browsing online (though it is indeed a lot!)6. When I was exploring mass timber, I had difficulty finding many useful sources (the ones I did find were indeed long PDF’s on 2000’s-style government websites). But the 30-minute conversations I was able to have with people who had actually went through the process of building a mass timber building were far more enlightening. Especially for newer industries, or those that are farther away from tech cultures, there’s often a large legibility gap between the reality on the ground and what people are willing to invest time and effort to put online7.

There is also something irreplaceably delightful about engaging with someone who has actually built something, rather than reading soulless PDF’s, which have been sanitized of personality and personal experience.

Indeed, even the best guides and references online are those who have real-world experience and have taken the significant investment of actually sharing and writing their experiences for the rest of us to learn from. They tend to be found on wordpress blogs and random reddit threads, and never have more than 25k followers on Twitter. Folks like Alon Levy for public transit or this Medium article by a truck driver during the supply chain crisis are good examples.

There is indeed a wealth of information online and learning how to navigate and utilize it is a powerful skill. But the best guides are still people8.

Safe travels on your digital journeys!

Nadia Asparouhova’s recent essay on the different tribes in climate is a great example of this for the climate space

For instance, places like Congressional Research Service or the National Academy of Sciences, which took me awhile to find but now I consistently go to.

And this is a fundamentally human process because everyone is looking for different types of knowledge, with different types of values embedded in them. For any useful question, there is no universal truth, which means you have to synthesize information and make your own judgements.

Tldr is that hydrogen will diffuse through anything

For a long time it was unclear what the best solar technology was: monocrystalline, polycrystalline, CdTe, etc. But monocrystalline was the incumbent and destroyed the other technologies market share because they got on the learning curve first and never stopped.

Except in fields like programming, math, and maybe physics. In those fields, you can probably get pretty far without ever talking to anyone (though for many reasons it’s probably more helpful if you do). I’ll explore the implications of the legibility gap between differentfields and ChatGPT in a later post

There’s a good example of this in the Star Wars TV Show Andor. (Spoiler) In episode 5, there’s a clip where the Rebel team asks Andor a question and its clear to him that they have no idea what the answer is. Andor knows the answer because he actually has experience, whereas the rest of the team was basing their entire knowledge on “the manual”, showing how inexperienced the team was and how badly they needed Andor’s help.